Streams in Scala - An Introductory Guide

Why Streams

There are many reasons for using a stream-processing approach when writing software. In this blog post I’m going to focus on just one of those reasons: Memory Management.

By processing elements one at a time streams enables you to avoid loading the entire dataset into memory and reducing the risk of encountering the dreaded 'Out of memory' error. Streams provide a lazy evaluation mechanism where elements are computed on-demand rather than being eagerly evaluated and stored in memory. This lazy evaluation, retaining only the necessary elements in memory, allows for efficient memory utilization especially when dealing with large datasets or potentially infinite sequences of data. With streams, you can confidently tackle memory-intensive tasks, knowing that the memory footprint is optimized, leading to more stable and scalable applications.

If you’ve ever run a program that has thrown the infamous Out Of Memory Error (OOM) then you’re going to appreciate the power of streams in Scala.

Let’s take a look at an example. What would be the result of running this code:

val sum =(1 to 10000)

.map(_ => Seq.fill(10000)(scala.util.Random.nextDouble))

.map(_.sum)

.sumThe above code would result in java.lang.OutOfMemoryError: GC overhead limit exceeded. When the above snippet is ran, the jvm tries to allocate memory for the elements of the range and the first transformer ( map operation ) is called immediately, which also tries to allocate memory for each element in the map. In total, we end up having 100,000,000 elements which the jvm needs to allocate memory for in the heap space which exceeds the maximum heap size specified through the -Xmx flag on the jvm.

The "GC overhead limit exceeded" error is an error message commonly encountered in Java Virtual Machine (JVM) based applications. This error occurs when the garbage collector is spending an excessive amount of time collecting garbage with little memory reclaimed. This error message is essentially an indication that the JVM is struggling to free up enough memory, and the application’s performance is significantly impacted. It typically occurs when the garbage collector is running continuously, consuming an excessive amount of CPU time. To prevent the garbage collector from consuming an excessive amount of CPU time with little benefit, the JVM defines a threshold known as the "GC overhead limit." Once this is reached, An error is thrown.

How would we avoid running into this kind of error? Whilst we can consider increasing the heap size allocated to the JVM using the -Xmx flag, I would strongly discourage this as it doesn’t fix the problem when we have more data or infinite data. This is where streaming comes in!

If your applications continuously require you to scale vertically ( increase the memory allocated to the application ) then you may want to consider building such application the streaming way. This will help you save cost and also make your application more stable.

The above code would be rewritten to the following:

val sum =(1 to 10000).toStream

.map(_ => Seq.fill(10000)(scala.util.Random.nextDouble))

.map(_.sum)

.sumThe above fixes the issue. It’s the same task but with the use of toStream. What changed? Chaining toStream made ( 1 to 10,000 ) not to be computed ( 1,2,3…10000) when the code is run except when it is required, So what will see when you output ( 1 to 10000).toStream ? you will see something like Stream(1, <not computed>). So the next question would be, when is an element of a stream required? An element of a stream is required when you call terminating operations like sum, size, foldleft,toList,toArray,foreach,reduce,foldLeft / foldRight,max / min,size,isEmpty. These operations require one element after the other from the stream when it is called. One other thing you would notice if you ran that piece of code is that your IDE says that toStream is deprecated. We will also talk about this in the upcoming section.

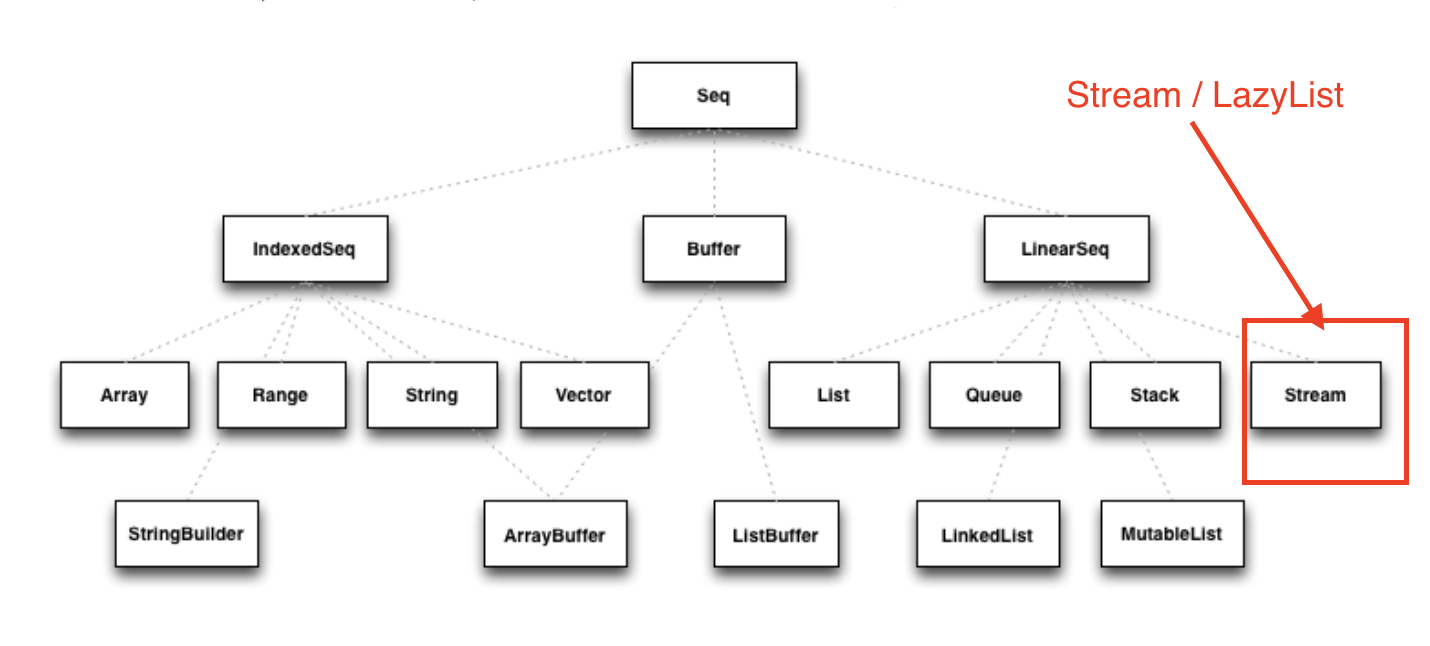

Scala Stream

Stream in Scala is part of the collection hierarchy which extends LinearSeq. They’re like views, only the elements that are accessed are computed. In views, elements are recomputed each time they’re accessed. In a stream elements are retained as they’re evaluated. Other than this behaviour, a Stream behaves similarly to a List. The elements of stream are lazily computed. In the Scala Stream, only the first element is pre-computed. As of Scala 2.13 Stream was replaced with LazyList where no element is computed unless requested. LazyList is designed to address the issues with Stream and provides a more predictable evaluation model.

// Scala prior to 2.13

(1 to 10000).toStream // output: Stream(1, <not computed>)

// Scala >= 2.13

(1 to 10000).to(LazyList) // output: LazyList(<not computed>)Transformer Vs Terminator method:

Transformer methods are collection methods, they’re part of the collections API. Transformer methods convert a given input collection to a new output collection, based on a function you provide which maps input to output. Examples of Transformer methods includes map, filter, and reverse.

Terminator methods are collection API methods which perform a final computation on a collection and return a non-collection result, such as an integer or a boolean value, for example. Terminator methods effectively terminate the computation and produce a final output. Examples of terminator methods include fold, reduce, and count.

Be careful with Terminator methods. Calls to these methods are evaluated immediately and can easily cause java.lang.OutOfMemoryError errors:

Call-by-name ( CBN )

While you can begin using LazyList collections with the information provided so far, I think it would also be good to have a basic understanding of the LazyList Implementation. Call-by-name (also known as pass-by-name) is a parameter evaluation strategy in programming languages where the argument expression is not evaluated before it is passed to a function or method. Instead, the expression is evaluated each time it is referenced within the function or method body. Just for note, the other parameter evaluation strategy is called, Call-by-value ( CBV )

When you create a LazyList, these are generalised summaries of the sequence of events.

// 1. The apply method is called from LazyList(1,2,3,4,5,7) which then calls the `from` implementation from LazyList companion object

def apply[A](elems: A*): CC[A] = from(elems)

// 2. Here, The 3rd case create an instance using the newLL method

def from[A](coll: collection.IterableOnce[A]): LazyList[A] = coll match {

case lazyList: LazyList[A] => lazyList

case _ if coll.knownSize == 0 => empty[A]

case _ => newLL(stateFromIterator(coll.iterator))

}

// And here is the type of parameter the newLL receives. It receives a call-by-name parameter!

/** Creates a new LazyList. */

@inline private def newLL[A](state: => State[A]): LazyList[A] = new LazyList[A](() => state)This portion ( state: ⇒ State[A] ) is called call-by-name. The state parameter has a return type of ⇒ State[A]. This parameter is not evaluated when passed, it’s only evaluated when a terminating method is called. So all transforming method operate on the state without it being called.

The same CBN is used as in the case below:

LazyList.cons(1, LazyList.cons(2, LazyList.empty))The parameters below are called call-by name

/** An alternative way of building and matching lazy lists using LazyList.cons(hd, tl).

*/

object cons {

/** A lazy list consisting of a given first element and remaining elements

* @param hd The first element of the result lazy list

* @param tl The remaining elements of the result lazy list

*/

def apply[A](hd: => A, tl: => LazyList[A]): LazyList[A] = newLL(sCons(hd, newLL(tl.state)))

/** Maps a lazy list to its head and tail */

def unapply[A](xs: LazyList[A]): Option[(A, LazyList[A])] = #::.unapply(xs)

}A Simple use-case of Scala Stream

Let’s consider a real-life scenario: Assume we are tasked with finding specific terms (e.g., success, failure, etc.) within large log files from various services running on our server. Our objective is to retrieve all occurrences of these terms and have the option to select the first few results. As you may know, Scala provides a Source API for reading files. In this task, we would compare two approaches and see why one is better than the other.

1st Attempt:

files.map {

case (file) =>

Source.fromFile(file).getLines().toList

.filter(_.contains("Success"))

.take(10)

}In the above snippet, we chained getLines and toList which ends up loading the content of the file into memory before filter is called. When we call toList, it evaluates immediately, and only after having read all lines from the file the filtering is applied. using a strict data structure like List would be a bad idea because of memory usage because the file could be large.

2nd Attempt:

files.map {

case (file) =>

Source.fromFile(file).getLines().to(LazyList)

.filter(_.contains("Success"))

.take(10)

}In the above snippet we chained getLines with to(LazyList). With this, the content of the files is not loaded into memory. We then apply the filter and take functions which still don’t load the content. The content of the file is only loaded when we call a terminating method like foreach. The benefit of this approach is that it only compute the first ten lines that match the filter predicate so that we don’t end up loading everything from file.

Alternative Libraries that implement Streams

Some Scala libraries offer enhanced stream processing capabilities compared to the LazyList API. These libraries are implemented following the Reactive stream standard. Reactive Streams is an initiative to provide a standard for asynchronous stream processing with non-blocking back pressure.

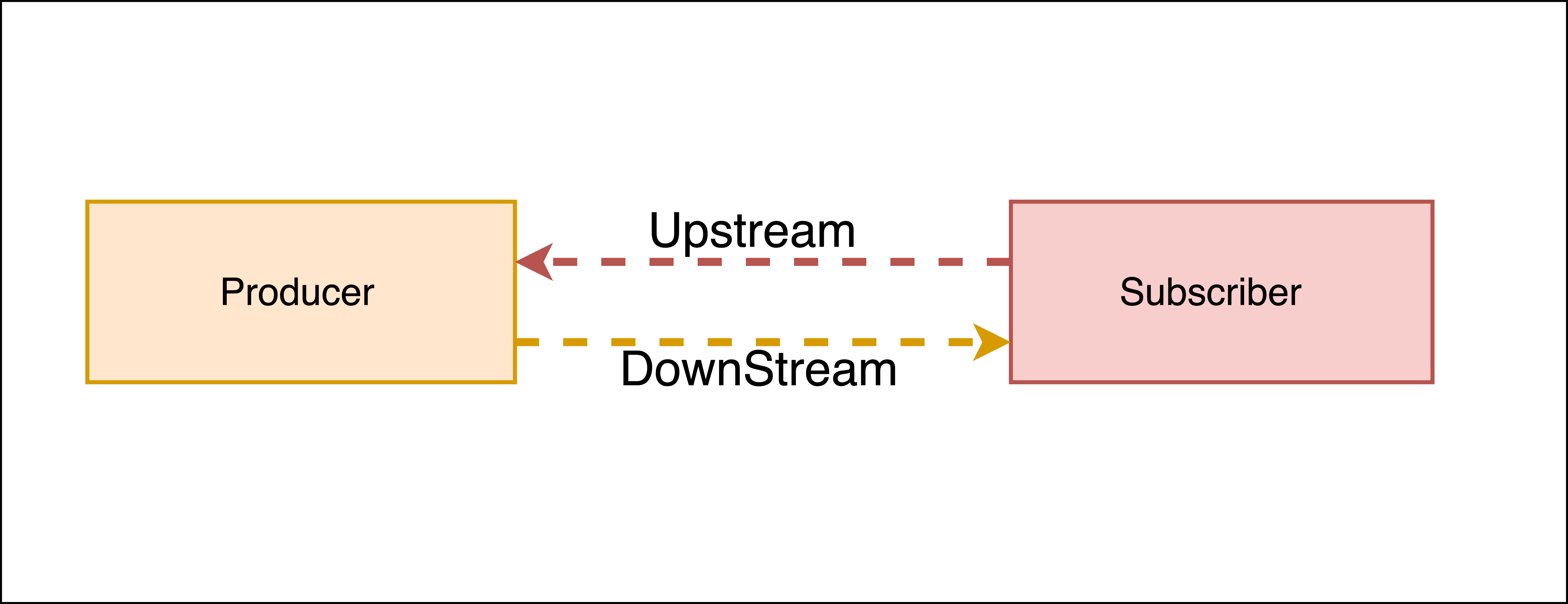

Reactive Stream

The Reactive Streams standard establishes two communication channels: an upstream demand channel and a downstream data channel. Publishers follow a request-based approach and only send data when a demand for a certain number of elements arrives through the demand channel. They can then push up to that requested number of elements downstream, either in batches or individually.

As long as there is outstanding demand, the publisher can continue pushing data to the subscriber as it becomes available. However, when the demand is exhausted, the publisher cannot send data unless prompted by a demand signal from downstream. This mechanism, known as backpressure, ensures controlled flow and prevents overwhelming the subscriber. In response to backpressure, the source can choose to allocate more resources, slow down its production, or even discard data.

To summarise, handling an un-bounded volume of data in an asynchronous system requires some form of control between the producer and the consumer otherwise we would have overwhelming data sent to the consumer from multiple threads. The Reactive stream standard introduces a concept of back-pressure which is a means of communication between the producers and the consumer. The reactive stream defines an interface which must be implemented.

The low-level interface of the Reactive streams:

trait Publisher[T] {

def subscribe(s: Subscriber[T]): Unit

}

trait Subscriber[T] {

def onSubscribe(s: Subscription): Unit

def onNext(t: T): Unit

def onError(t: Throwable): Unit

def onComplete(): Unit

}

trait Subscription {

def request(n: Int): Unit

def cancel(): Unit

}This interface is just a representation of the core components of reactive streams and the actual implementation is way harder and beyond the scope of this post. It’s recommended you make use of the high-level stream API

The below libraries take into account this reactive stream interface and implement high-level stream API

Akka Streams:

Akka Streams is a powerful and scalable stream processing library built on top of the Akka toolkit. It provides a high-level DSL for composing and executing stream-based computations. Akka Streams offers backpressure support, fault-tolerance, and integration with other Akka components. It’s widely used in building reactive and distributed systems.

fs2:

fs2 (Functional Streams for Scala) formerly called Scalaz-Stream is a functional stream processing library that provides a purely functional, composable, and resource-safe approach to handling streams. It leverages functional programming concepts such as cats-effect and functional abstractions to build complex stream processing pipelines. fs2 focuses on efficiency, type safety, and composability. Beyond stream processing, fs2 can be used for everything from task execution to control flow.

ZIO Streams:

ZIO Streams is part of the ZIO ecosystem, which is a powerful and purely functional library for building concurrent and resilient applications. ZIO Streams offers composable, resource-safe, and type-safe stream processing capabilities. It integrates well with other ZIO components, allowing you to build complex and concurrent stream-based workflows.

These libraries provide advanced features, performance optimizations, concurrent handling of data, proper error handling and additional abstractions for handling streams in Scala. Depending on your specific requirements and use case, you can choose the library that best aligns with your needs.

Conclusion

In this blog post we have seen how:

-

Scala’s

StreamandLazyListwork and how they can be used to process large data sets. We have also seen howLazyListare implemented with lazy evaluation -

The important distinction between

transformerandterminatorfunctions in the API -

Scala’s streams compare to other stream processing library’s stream implementations

I have prepared a repository that shows how to process large log files using LogStream ( Wrapper of Scala LazyList ), Akka stream, and Fs2 stream. You can find the repository here