Using Dotty Union types with Akka Typed - Part II

Introduction

After posting the first article on Using Dotty Union types with Akka Typed, I received valuable feedback via Twitter which made me decide to write this follow-up article. I will clean up a few loose ends and add some new insights.

Let’s take a bird’s eye view of this follow-on content.

Loose End - The Protocol Problem!

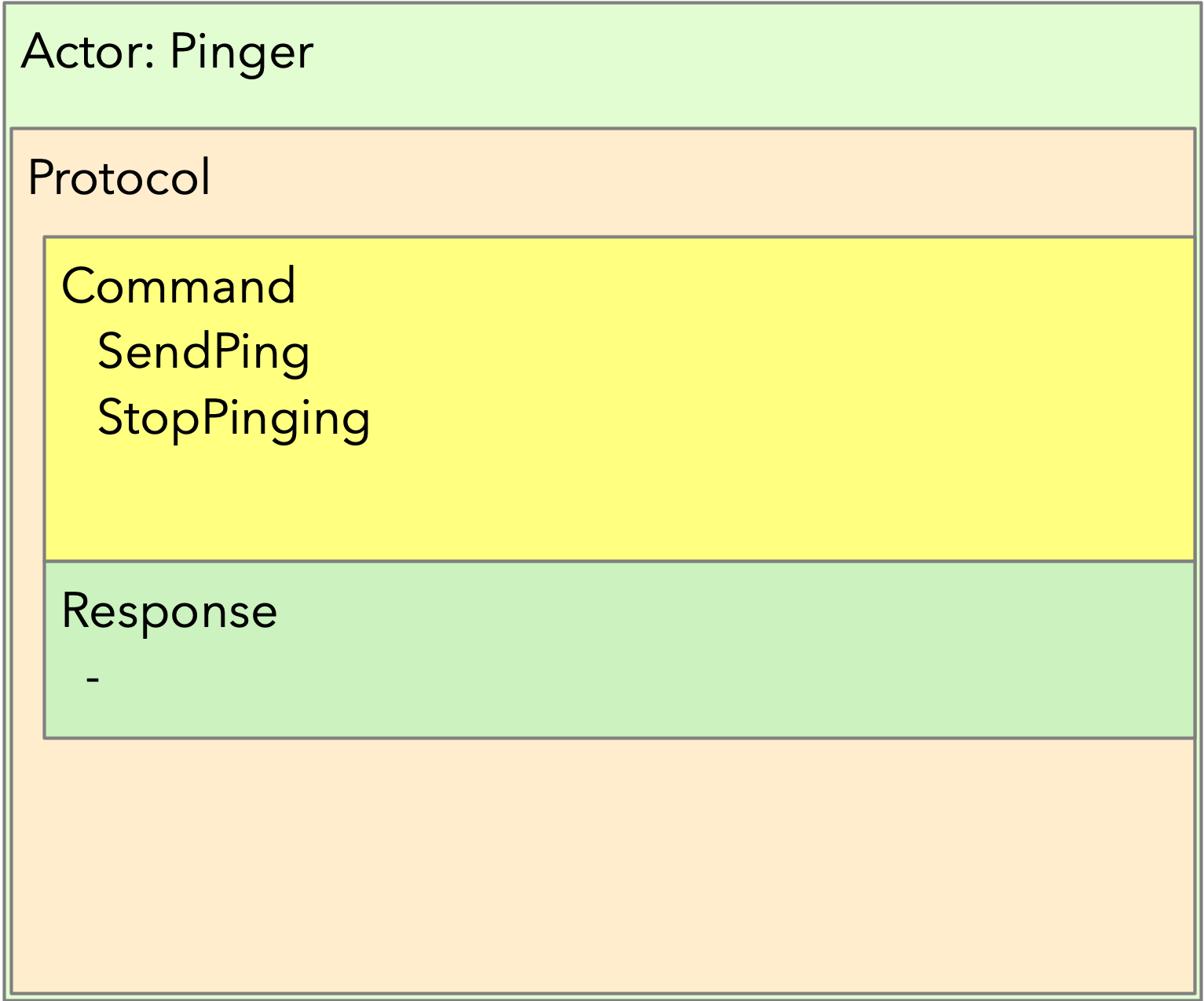

Both the Scala 2 and the Dotty version of the Pinger actor suffer from the same problem: the actor’s protocol has been unnecessarily widened. It should be narrowed back to the absolute minimum shown in figure 1.

-

In the Scala 2 version of the code, a message adapter is used that wraps the response from the

PingPongactor. As part of the implementation, aWrappedPongResponsemessage widens the actor protocol. -

In the Dotty version of the code, the protocol is widened with the

PingPong.Responsetype of messages (of which there is only one specific instance: thePingPong.Pongmessage).

Pinger actor protocolSolutions and insights

As a fix for the protocol problem, we use a method in the Akka 2.6 library, narrow, and we’ll look at how Dotty has the potential to simplify this approach.

Further Insights & Summary

I’ll finish up with summarising a few of the best practices for coding actors that are to a large extent based on the Akka Typed Style guide.

Restoring the Pinger actor’s protocol

Let’s have a look at the final version of the protocol of the Pinger actor using Scala 2.13 and Akka 2.6:

object Pinger {

sealed trait Command

case object SendPing extends Command

case object StopPingPong extends Command

final case class WrappedPongResponse(pong: PingPong.Response)

extends Command

...

}The problem should be obvious: we shouldn’t expose the WrappedPongResponse wrapper message as part of the Pinger actor’s protocol. In other words, we have unnecessarily widened the actor’s protocol by adding the publicly accessible WrappedPongResponse message to it.

Obviously, this is undesirable, and the fix in this case is quite simple: we can mark this message as private and we’re done:

object Pinger {

sealed trait Command

case object SendPing extends Command

case object StopPingPong extends Command

private final case class WrappedPongResponse(pong: PingPong.Response)

extends Command

...

}Restoring the Pinger actor’s protocol - Dotty version

The Dotty version of the Pinger actor suffers from the same problem. The protocol of the actor is widened with the PingPong.Pong message. This means that any actor can send a Pong message to the Pinger actor. The solution in this case is different from previous one:

-

The

applymethod in thePingerobject, will return aBehavior[Command]thus restoring the original protocol -

The

Pingeractor defines an internal behavior of typeBehavior[CommandsAndResponses] -

The

Behavior[Command]is derived from theBehavior[CommandsAndResponses]by applying thenarrowmethod on the latter

This leads to the following code:

object Pinger {

// My protocol

sealed trait Command

case object SendPing extends Command

case object StopPingPong extends Command

// My protocol + the responses I need to understand...

private type CommandsAndResponses = Command | PingPong.Response

def apply(pingPong: ActorRef[PingPong.Ping]): Behavior[Command] = {

val internalBehavior: Behavior[CommandsAndResponses] =

Behaviors.setup { context =>

Behaviors.receiveMessage {

case StopPingPong =>

context.log.info(s"End of the ping-pong game - calling it a day!")

context.system.terminate()

Behaviors.stopped

case SendPing =>

pingPong ! PingPong.Ping(replyTo = context.self)

Behaviors.same

case response : PingPong.Response =>

context.log.info(s"Hey: I just received a $response !!!")

Behaviors.same

}

}

internalBehavior.narrow

}

}Admittedly, some magic has happened here and the question to ask is, What is this narrow method doing? Let’s look at that in the next section.

Clearing up some magic

The Behavior abstract class in Akka 2.6 defines the narrow method, and here is a part of the relevant source code:

abstract class Behavior[T](private[akka] val _tag: Int) { behavior =>

/**

* Narrow the type of this Behavior, which is always a safe operation. This

* method is necessary to implement the contravariant nature of Behavior

* (which cannot be expressed directly due to type inference problems).

*/

final def narrow[U <: T]: Behavior[U] = this.asInstanceOf[Behavior[U]]

...

}

abstract class ExtensibleBehavior[T] extends Behavior[T](BehaviorTags.ExtensibleBehavior) {

...

def receive(ctx: TypedActorContext[T], msg: T): Behavior[T]

...There’s quite a bit going on here.

First, we note that the Behavior class is generic: it has a type parameter T, which, because of no specific variance annotation on T, implies that Behavior is invariant in its type parameter T. Also note the comment on the narrow method, stating:

This method is necessary to implement the contravariant nature of Behavior (which cannot be expressed directly due to type inference problems).

Second, we see that the class ExtensibleBehavior, which is a subclass of Behavior, has a receive method which takes a parameter msg of type T. Because functions (or methods), are contravariant in their argument types, the only possible variance case for the type parameter is invariant (T) or contravariant (-T). Because of type inference problems in Scala 2, the former was chosen.

|

Note

|

Variance manifests itself in specific contexts and is a big topic in itself with contravariance being the least intuitive. We’ll see however that, in the case of Behavior, it is actually quite easy to understand. I’ll get back to that later. For a comprehensive explanation of variance in Scala read this article.

|

Finally, we see from the definition of the narrow method, that it returns a behavior which is more restrictive in its type than the behavior on which it is called. The implementation of narrow uses asInstanceOf to apply this restriction.

Clearing up some magic in the context of Dotty

All the above is nice, but it will leave some readers with questions. So, let’s look at this from a practical point of view by looking at the Dotty version of the Pinger which uses Union types.

Starting from the (internal) protocol definition:

object Pinger {

sealed trait Command

case object SendPing extends Command

case object StopPingPong extends Command

// My protocol + the responses I need to understand...

type CommandsAndResponses = Command | PingPong.Response

}

object PingPong {

sealed trait Command

final case class Ping(replyTo: ActorRef[Response]) extends Command

sealed trait Response

case object Pong extends Response

}We can run the following experiment (in dotr, the Dotty REPL):

scala> import akka.actor.typed.ActorRef

scala> object Pinger {

| sealed trait Command

| case object SendPing extends Command

| case object StopPingPong extends Command

|

| // My protocol + the responses I need to understand...

| type CommandsAndResponses = Command | PingPong.Response

| }

|

| object PingPong {

| sealed trait Command

| final case class Ping(replyTo: ActorRef[Response]) extends Command

|

| sealed trait Response

| case object Pong extends Response

| }

// defined object Pinger

// defined object PingPong

scala> summon[Pinger.Command <:< Pinger.CommandsAndResponses]

val res0: Pinger.Command =:= Pinger.Command = generalized constraintThe fact that the last command returned a generalized constraint means that Pinger.Command is a subtype of Pinger.CommandsAndResponses or, differently expressed: an instance of Pinger.Command can be considered as being an instance of Pinger.CommandAndResponses.

Imagine now that Behavior is defined as contravariant in its type parameter T (and define it as a trait instead of an abstract class in the Akka source code so that for this demo, we can easily create an instance of it).

scala> trait Behavior[-A] {}

scala> summon[Behavior[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses] <:< Behavior[Pinger.Command]]

val res1: Behavior[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses] =:=

Behavior[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses] = generalized constraintThe last line in the dotr session tells us that an instance of Behavior[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses] can be considered to be an instance of Behavior[Pinger.Command]. This allows us to do the following:

// We can mark the following variable as private, but this doesn't work in the REPL

scala> val internalBehavior = new Behavior[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses] {}

val internalBehavior: Behavior[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses] = anon$1@8f221a7

scala> val externalBehavior: Behavior[Pinger.Command] = internalBehavior

val externalBehavior: Behavior[Pinger.Command] = anon$1@8f221a7Let this sink in for a second… We have achieved something important: we derived our externalBehavior from the more specific internalBehavior by using the type system and appropriate variance definitions and this without having to apply the narrow method!

Does this make sense intuitively? It does: externalBehavior is declared as a behavior that is able to 'process' all messages that are part of the Pinger actor’s Command protocol. The behavior that is actually handling these messages is the internalBehavior which, on top of the messages of type Command, is able to process the PingPong.Pong message.

|

Note

|

One could say that from the outside, the internal behavior is not utilised to its full extent. |

The combination of Dotty Union types combined with the generic Behavior of having a contravariant type parameter leads to a very simple implementation of the Pinger actor. The future will tell if, with Dotty, Akka will be able to exploit this in a future version.

Returning to best practices for coding up actors in Akka Typed

The coding style I’m using is drawn from the Akka Typed Style guide. This guide leaves some choices to the programmer such as choosing between an object oriented style or a functional style. For the functional style, I prefer to put the core behavior of a typed actor in a companion class. An advantage of this approach is that the method that will return the initial behavior doesn’t have to take extra contextual parameters that need to be passed in: these can be added as class parameters. In simple cases, that may be considered overkill, but as a counter argument, I think that applying the same practice in a consistent manner helps to maintain a recurring and easily recognisable way of coding actors.

The Dotty version of the Pinger actor will then look as follows:

import akka.actor.typed.{ActorRef, Behavior}

import akka.actor.typed.scaladsl.{ActorContext, Behaviors}

object Pinger {

// My protocol

sealed trait Command

case object SendPing extends Command

case object StopPingPong extends Command

// My protocol + the responses I need to understand...

private type CommandsAndResponses = Command | PingPong.Response

def apply(pingPong: ActorRef[PingPong.Ping]): Behavior[Command] = {

val internalBehavior = Behaviors.setup[CommandsAndResponses] { context =>

(new Pinger(context, pingPong)).run()

}

internalBehavior.narrow

}

}

class Pinger private (context: ActorContext[Pinger.CommandsAndResponses], pingPong: ActorRef[PingPong.Ping]) {

import Pinger._

def run(): Behavior[CommandsAndResponses] =

Behaviors.receiveMessage {

case StopPingPong =>

context.log.info(s"End of the ping-pong game - calling it a day!")

context.system.terminate()

Behaviors.stopped

case SendPing =>

pingPong ! PingPong.Ping(replyTo = context.self)

Behaviors.same

case response : PingPong.Response =>

context.log.info(s"Hey: I just received a $response !!!")

Behaviors.same

}

}Note that we prevent the direct creation of instances of the Pinger actor by marking the constructor of the Pinger class private.

Conclusions

In this article:

-

I have shown in both Scala 2 and Dotty how to handle responses sent to other actors without unnecessarily widening the message protocol:

-

In Scala 2, we can use message adapters where the message wrapper is marked private.

-

In Dotty, we can use the

narrowmethod onBehavior.

-

-

we looked at a potential alternative to

Behavior.narrowwhich may become reality sometime in the future. -

we concluded with a look at best practices to code an Actor using Akka Typed.

A big thanks to all people who reviewed this article: my colleagues at Lunatech, Leonor Boga, Chris Kipp, Pedro Ferreira and my former colleague Kiki Carter!